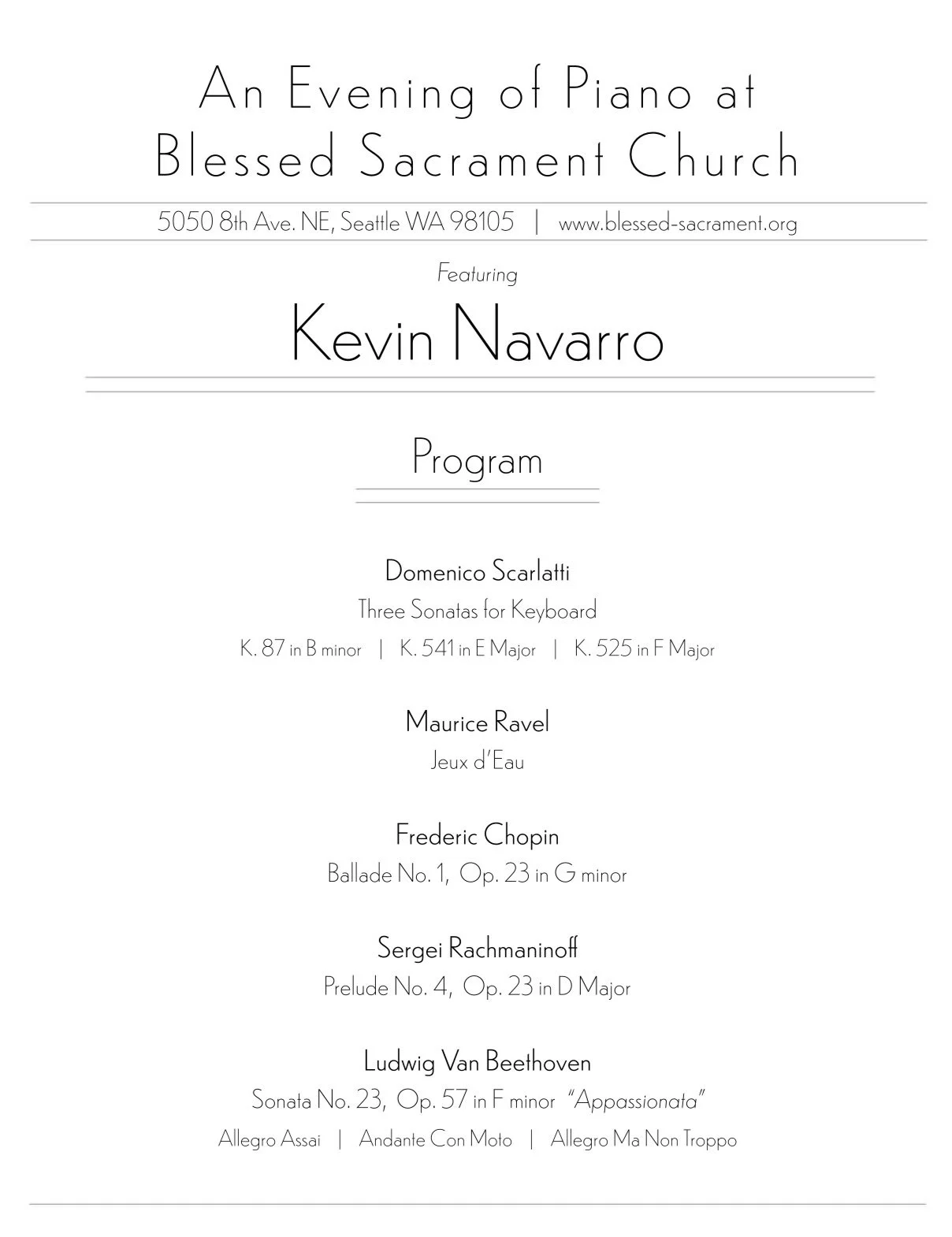

Program Notes

Domenico Scarlatti

Three Sonatas for Keyboard

Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757), an Italian composer, occupies a fascinating transitional space in music history. While chronologically placed within the Baroque Era, his innovative spirit and unique keyboard writing significantly foreshadowed and profoundly influenced the burgeoning Classical style. He is particularly celebrated for his pivotal contribution to the sonata form, a structural cornerstone of Western music. As the son of the renowned composer Alessandro Scarlatti, Domenico distinguished himself by composing an astounding 555 keyboard sonatas.

During the Baroque period (roughly 1600–1750), the sonata form, as we understand it today, did not yet hold a central position. Although only a fraction of Scarlatti's immense creative output was published during his lifetime, his complete collection of sonatas was deeply admired by subsequent generations of composers who recognized their groundbreaking nature and elevated the sonata form to a foundational element of musical architecture. These admirers included such luminaries as Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven. Even Frédéric Chopin, a leading voice of the Romantic Era, held Scarlatti's work in high esteem, privately teaching and performing these sonatas for his students. Chopin famously observed, "My colleagues, the piano teachers, are dissatisfied that I am teaching Scarlatti to my pupils. But I am surprised that they are so blind. In his music there are exercises in plenty for the fingers and a good deal of lofty spiritual food. If I were not afraid of incurring disfavor of many fools, I would play Scarlatti in my concerts. I maintain there will come a time when Scarlatti will often be played in concerts, and people will appreciate and enjoy him."

Tonight's program features three distinct examples of Scarlatti's remarkable keyboard sonatas:

The opening piece, Sonata in B Minor, K. 87, stands as a particularly poignant work, imbued with a profound sense of soulful resignation. Scarlatti masterfully evokes this deep sorrow through the prominent use of suspensions, creating a musical landscape that conveys a tragedy not of anguished cries, but of a weary acceptance, a burden borne for far too long.

Following this is the Sonata in E major, K. 531, a captivating piece celebrated for its elegantly expressive melody and harmonic inventiveness. This sonata, a gem within Scarlatti's vast collection, shines with its bright tonality and intricate embellishments. It serves as an exquisite illustration of Scarlatti's unique ability to seamlessly blend Italian and Iberian musical traditions within the solo keyboard idiom.

The program concludes with the Sonata in F Major, K. 525, a lively and engaging piece characterized by its bright and energetic melodies. Marked "Allegro," this sonata is a quintessential example of Scarlatti's virtuosic keyboard writing and his talent for creating a sense of playful exuberance. Its fast-paced, almost relentless rhythmic drive strongly suggests the vibrant energy of a Spanish dance, perhaps echoing the fiery spirit of the bulería.

Maurice Ravel

Jeux d'Eau

Joseph Maurice Ravel (1875–1937) stands as a pivotal figure in French music, celebrated as a gifted composer, pianist, and conductor. While often associated with the Impressionist movement alongside his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, Ravel himself, like Debussy, resisted this categorization. By the 1920s and 1930s, Ravel had achieved international recognition as France's preeminent living composer.

Born into a musically inclined family, Ravel pursued his formal training at France's leading music institution, the Paris Conservatoire. However, his artistic vision often clashed with the conservative establishment, whose perceived bias against him led to considerable controversy. Following his departure from the Conservatoire, Ravel forged his own distinct compositional path, cultivating a style marked by remarkable clarity. His musical language embraced elements of modernism, baroque aesthetics, neoclassicism, and, in his later works, the vibrant rhythms and harmonies of jazz. Notably, Ravel was among the first composers to recognize the transformative potential of recording technology in disseminating their music to a wider audience. From the 1920s onward, despite acknowledging his own limitations as a pianist and conductor, he actively participated in recordings of several of his compositions, while others were meticulously made under his direct supervision.

Ravel's early, significant contribution to the piano repertoire, Jeux d'eau (1901), is frequently cited as evidence of his independent stylistic evolution, predating the major piano works of Debussy. In his writing for solo piano, Ravel generally eschewed the intimate, chamber-like textures often found in Debussy's work, instead aiming for a Lisztian virtuosity and brilliance. The evocative title translates variously as "Fountains," "Playing Water," or literally "Water Games." At the time of its composition, Ravel was a student of Gabriel Fauré, to whom this captivating piece is dedicated. Jeux d'eau holds a strong claim to being the first true example of musical Impressionism in piano literature. The piece is renowned for its virtuosic demands, its fluid and shimmering textures, and its highly evocative nature, solidifying its place as one of Ravel's most important works for the piano. Characterized by rapid, cascading piano figurations, the music vividly conjures the sound and visual imagery of flowing water. The overall atmosphere of Jeux d'eau is one of lightness, playfulness, and sensuousness, often described as a musical depiction of the joy and inherent beauty of the natural world. Jeux d'eau stands as a masterful example of Ravel's distinctive compositional voice, marked by its clarity of line, meticulous precision, and exquisite sensitivity to color and texture.

Frederic Chopin

Ballade No. 1, Op. 23 in G Minor

Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849) reigns as a monumental figure of the Romantic era, his name synonymous with profound musicality and an unparalleled virtuosity at the piano. Primarily a composer for his own instrument, his "poetic genius" was underpinned by a technical command that astounded his contemporaries.

Chopin's enduring legacy as a groundbreaking pianist and the creator of some of the Romantic era's most iconic piano literature is particularly striking given his limited public appearances. Achieving such widespread and lasting acclaim with a mere 30 official concerts speaks volumes about the transformative impact of each of those rare occasions. Considered by many to be the preeminent pianist of his generation, Chopin possessed a technical brilliance matched by a singular ability to communicate directly with the emotional core of his listeners. In a 19th-century world where opportunities to experience exceptional performers were far fewer than today, the significance of witnessing a Chopin performance must have been truly immense. These appearances, coupled with his strikingly original solo piano compositions, firmly established him as one of the most influential musicians of his age.

While the term "ballade" originated in 14th-century French poetry as a narrative form, it was the composers of the 19th century who embraced it as a purely instrumental genre, using musical language to evoke storytelling. Chopin composed his four ballades during his mature period, after his departure from his beloved Poland. These works are masterpieces of pure musical expression, transcending any specific intended narrative. An understanding of a particular poetic inspiration is not a prerequisite for appreciating the abstract beauty and profound emotional depth inherent in these compositions. Each of the four ballades is a substantial work, typically ranging from 8 to 12 minutes in performance, written in triple meter (6/4 or 6/8), and characterized by their poetic, dramatic, and contrasting thematic material. While sharing these general characteristics, each ballade stands as a distinct and individual creation, not conceived or intended to be performed as a unified set – a sentiment echoed by Chopin himself. In each ballade, he meticulously developed unique musical ideas and combined them with innovative harmonic shifts, often incorporating and reimagining classical forms such as sonata, rondo, and variations with remarkable flexibility. The ballades thus represent a compelling synthesis of traditional structural elements and a highly original expressive voice, all within the broad framework of classical principles.

The Ballade No. 1 in G minor, Op. 23, completed in 1835, stands as one of Chopin's most cherished and frequently performed compositions. Its genesis can be traced back to sketches from 1831, during Chopin's eight-month stay in Vienna. He finalized the Ballade after his arrival in Paris, dedicating it to Baron Nathaniel von Stockhausen, the Hanoverian ambassador to France. Following a meeting with Robert Schumann in Leipzig in the autumn of 1836, Schumann eloquently captured the essence of the work, writing: "I have a new Ballade by Chopin. It seems to me to be the work closest to his genius (though not the most brilliant). I even told him that it is my favourite of all his works. After a long, reflective pause he told me emphatically: 'I am glad, because I too like it the best, it is my dearest work.'"

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Prelude No. 4, Op. 23

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) stands as a monumental figure in the world of classical music, revered as a Russian composer of profound emotional depth, a piano virtuoso of legendary status, and a distinguished conductor. Widely considered one of the finest pianists of his era, Rachmaninoff also holds a significant place in music history as one of the last great representatives of Romanticism within the Russian classical tradition.

Born into a family with strong musical roots, Rachmaninoff began his piano studies at the remarkably young age of four. He further honed his skills in both piano performance and composition at the prestigious Moscow Conservatory, graduating in 1892 with a substantial body of compositions already to his name. However, in 1897, the disastrous premiere of his Symphony No. 1 plunged Rachmaninoff into a four-year period of depression and creative silence. It was not until supportive therapy enabled him to complete his universally acclaimed Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1901 that his compositional output resumed. Rachmaninoff subsequently held the esteemed position of conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre from 1904 to 1906 before relocating to Dresden, Germany, in 1906. In 1909, he embarked on his first concert tour of the United States as a pianist, marking the beginning of his significant international career. Following the upheaval of the Russian Revolution, Rachmaninoff and his family left Russia permanently, making their home in New York City in 1918. For the remainder of his life, he dedicated the majority of his time to touring as a celebrated pianist throughout the United States and Europe.

The piano occupies a central and prominent role in Rachmaninoff's compositional output, and he masterfully utilized his own extraordinary performing abilities to fully explore the expressive and technical possibilities of the instrument. Rachmaninoff's early compositional style bore the clear influence of Tchaikovsky. However, by the mid-1890s, his works began to reveal a more distinct and individual voice. His First Symphony, despite its initial negative reception, showcased many original features. Its stark intensity and uncompromising expressive power were unprecedented in Russian music of the time. Furthermore, its flexible rhythms, sweeping lyrical melodies, and stringent economy of thematic material were all hallmarks that he retained and refined in his subsequent compositions. Following the setback of the symphony's reception and a subsequent three-year period of limited creative activity, Rachmaninoff's individual style underwent significant development. He increasingly gravitated towards broadly lyrical, often intensely passionate melodies. His orchestration became more nuanced and varied, with carefully contrasted textures. Overall, his writing evolved towards greater conciseness and focus.

Unlike Chopin, who famously composed his set of 24 Preludes, Op. 28 (1838), in a relatively short period, Rachmaninoff dedicated a span of 18 years to the completion of his own set of 24 Preludes. These were published in two collections – 10 Preludes, Op. 23 (1903), and 13 Preludes, Op. 32 (1911) – with one additional prelude composed in isolation. Tonight's offering, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in D Major, Op. 23, No. 4 (Andante cantabile), is a captivating and dreamlike nocturne cast in triple meter. Its sensuous melody gracefully unfolds above continuous, gently undulating waves of eighth notes. Moving seamlessly between moments of intimate expression and soaring passion, the prelude takes the listener on a journey marked by revelatory harmonic shifts. The central melody sings out from within the rich texture, initially enveloped by a shimmering sonic halo of bell-like overtones. This is then enriched by a gently flowing descant in the higher register, and finally crowned with echoing, chime-like figures in the uppermost reaches of the piano.

Ludwig Van Beethoven

Sonata No. 23, Op. 57 "Appassionata"

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) stands as a titan among composers, particularly revered as the supreme master of the Classical sonata form. His monumental collection of 32 piano sonatas, composed between 1795 and 1822, has earned a legendary status. The esteemed pianist Hans von Bülow aptly declared, "Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier is music's 'Old Testament', and Beethoven's Piano Sonatas are music's 'New Testament'," highlighting their profound historical significance and enduring influence. These works not only inspire but also established new compositional standards and forms that continue to be studied and emulated by musicians across generations.

From 1770 to 1827, Beethoven's impact irrevocably altered the course of musical composition and style. His influence on the Classical Era was transformative, paving the way for the emergence of the Romantic Era. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Beethoven primarily composed according to his own artistic vision, often diverging from the prevailing musical tastes. His style was characterized by a richer texture and tone, a grander scale, and a more potent expression of emotion that often transcended traditional formal constraints. He expanded the traditional orchestra and even introduced a choir into his groundbreaking Ninth Symphony.

As a performer and conductor, Beethoven faced increasing challenges due to his progressive hearing loss, which began around the age of 26. In a poignant letter to a friend, he described his "peculiar deafness," noting his difficulty in hearing high notes and soft speech, while loud sounds became unbearable. This personal struggle, marked by turmoil and frustration, profoundly impacted his compositions during this period.

The "Appassionata," often considered Beethoven's greatest piano sonata before the "Hammerklavier," revolutionized the form. His student, Carl Czerny, even noted that Beethoven himself held this view. The sonata's ominous "fate phrase" at the beginning, echoing the mood of the Fifth Symphony, returns to close the first movement after a ferocious coda, creating an atmosphere of panic and instability. The chaotic first movement is followed by an unexpectedly serene variation on a theme, seemingly lulling the listener into a false sense of tranquility. Just when a final chord in D-flat major seems imminent, Beethoven disrupts this expectation with a powerful diminished seventh chord, abruptly reigniting the frantic energy of the first movement. The aggressive and relentless pace of the third movement, driven by relentless sixteenth-note passages, culminates in one of his most powerful codas, bringing this monumental work to a close. When questioned about the meaning of the "Appassionata," Beethoven reportedly advised, "Read Shakespeare's Tempest."

By 1814, at the age of 44, Beethoven was almost completely deaf. Yet, until his death in 1827, he continued to create some of his most profound works, including his last five piano sonatas (most notably the "Hammerklavier"), the Missa Solemnis (a rare choral Mass), and the Symphony No. 9 for Full Orchestra and Chorus, a pinnacle of musical achievement.